Guest post: "The Bionic Elbow: On Fathers, Sons, and the American Dream" by Michael Chin

"It was my grandfather who drew my father into wrestling, after which my father introduced it to me." - Michael Chin

Occasionally on “when hope writes” I’ll publish guest posts by brilliant artists and writers. If you want to be a guest blogger on my Substack, please connect with me on Facebook, LinkedIn, or my website.

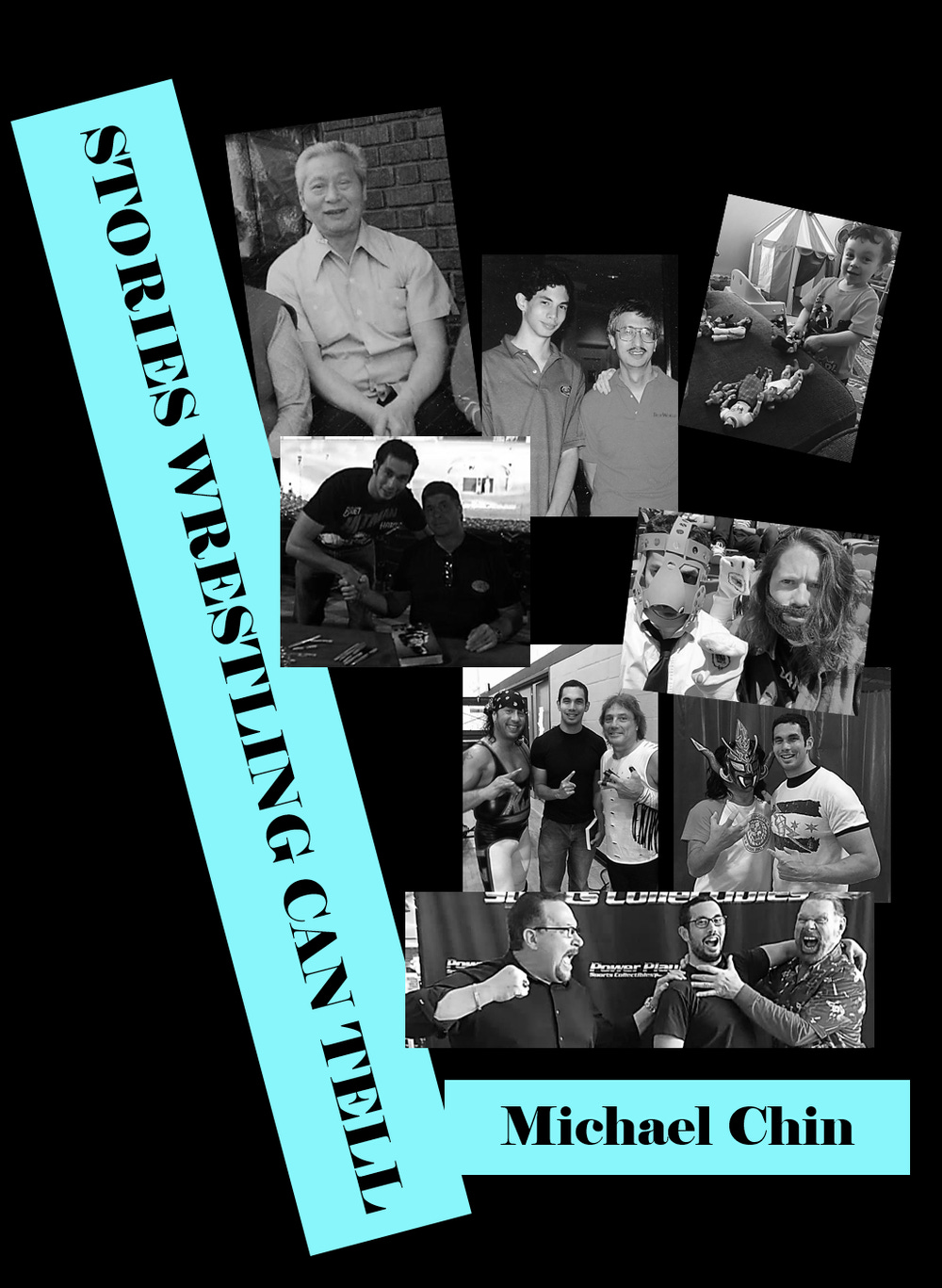

Today I’m sharing a touching and thought-provoking autobiographical essay titled “The Bionic Elbow: On Fathers, Sons, and the American Dream” by the remarkable writer Michael Chin. “The Bionic Elbow: On Fathers, Sons, and the American Dream” was previously published at Longridge Review. It is part of a larger project called Stories Wrestling Can Tell.

In professional wrestling, every star has a finisher. It’s a signature move or hold that tends to result in victory, and particularly so in the biggest moments a performer’s career. Hulk Hogan lowered his leg drop on Andre the Giant to pin him in front of a live crowd of ninety-thousand-plus at WrestleMania 3. Sting has his Scorpion Deathlock that he used to relieve Hogan of the World Championship at a Starrcade super show ten and a half years later. Goldberg would plant Sting with the Jackhammer at Halloween Havoc two years after that.

And then there’s Dusty Rhodes. Rhodes had a finisher—The Bionic Elbow—which was really little more than Rhodes smashing his elbow against an opponent’s skull, usually after a series of jukes and hand-jiving. But it’s fitting that Rhodes’s finisher would be more sizzle than steak because the man himself was always less famous as an in-ring performer than as a pro wrestling personality. More of a talker than an athlete.

Rhodes won world championships on three separate occasions—most famously pinning arch-rival Ric Flair. But when he achieved that culminating in-ring moment, it wasn’t the Bionic Elbow that sealed the deal, but rather a small package—a pinning predicament designed to hold an antagonist’s shoulders to the mat just long enough for the referee to count to three. A feeble offensive formation that most wresters kick out of most of the time. A pin that always surprises audiences when it actually works.

And so, there’s no real iconic image of Rhodes vanquishing a foe to accompany his in-ring career highlight. Instead, Rhodes’s biggest moment remains linked to his monologue, delivered in a Texas accent, inflected by a speech impediment that he had a habit of bulling his way through, turning s- sounds to th-s. It’s been called the “Hard Times” promo, in which Rhodes, building to a confrontation with Flair, likened the flamboyant champion and his cronies to big businesses of the day that oppressed and laid off workers.

Hard times are when the textile workers around this country are out of work, they got four or five kids and can’t pay their wages, can’t buy food. Hard times are when the auto workers are out of work and they tell ‘em to go home. And hard times are when a man has worked at a job for thirty years—thirty years!—and they give him a watch, kick him in the butt, and say “hey, a computer took your place, daddy.” That’s hard times. That’s hard times. And Ric Flair, you put hard times on this country by taking Dusty Rhodes out, that’s hard times … the World’s Heavyweight title belongs to these people.

Such was the ethos of Rhodes, whose two most oft used nicknames were “The Son of a Plumber” (which he literally was) and “The American Dream.”

*

My father’s family subscribed to the American Dream. Not Dusty’s vision, per se, but the more conventional take of heading to the States and making a life on hard work and a can-do attitude. His parents were Chinese immigrants who came across the Atlantic with minimal English vocabulary. Be it lack of opportunities, limited skill in learning a new language, or a stubborn resistance to assimilate, they never did learn even the fundamentals. But they opened a laundromat and they raised three sons, each of whom would speak English fluently.

But perhaps it’s because he couldn’t speak the language that my grandfather was drawn to professional wrestling. Ostensibly a sport, and one with so few rules, and such clear lines between good guys to cheer and bad guys to jeer that he didn’t need the English language to follow what was happening, just eyesight to see the fights and a sense of hearing to follow who the crowd was rallying for and against.

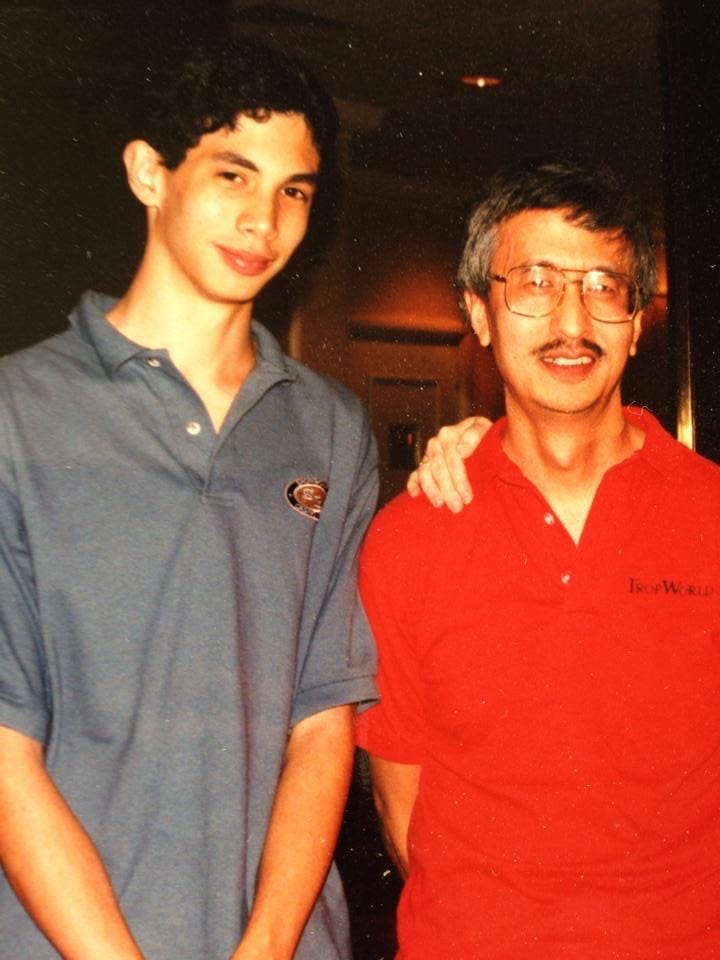

It was my grandfather who drew my father into wrestling, after which my father introduced it to me.

My father would have aspirations beyond the laundromat. He’d be the first in the family to go to college, then the first to earn a graduate degree. He was the second to marry, but first, again, when it came to leaving New York City and having children.

Before all that, Dad sat by the window at his father’s laundromat to grapple his way through word problems and study self-made flash cards about American history. It was in one of these spates of study that a photographer from Life Magazine saw him and his brothers, and took their picture to accompany an article about a new wave of immigrants trying to make it in the States. My grandmother still has the 1957 issue with that photo—that black and white picture that captures my father as a grade-schooler—the embodiment of the American Dream.

*

I first encountered Dusty Rhodes on the cover of a magazine—the November 1989 issue of Pro Wrestling Illustrated that I have distinct memories of seeing in the magazine aisle at a Price Chopper and leafing through while my grandmother shopped for a greeting card for her friend’s birthday. At six years old, I’d only recently learned to read, and though I suspect this wasn’t actually my first encounter with a wrestling magazine, I remember it as a particularly satisfying one. Encountering text that I could newly understand, not telling a children’s story, but the stories of wrestling matches broadcasted in other parts of the country, other parts of the world. And this peculiar, doughy man with a physique nothing like my idol, the musclebound Hulk Hogan, who was nonetheless, himself, in world title contention.

It occurs to me now that there’s every possibility it wasn’t just I who encountered Rhodes through magazine pages, but his son Dustin, too, who went on to be a wrestler as well, and went on to have a meaningful relationship with his father, but who has nonetheless spoken of growing up father-less, his old man on the road more often than not, earning a living dropping elbows and talking about the American Dream from city to city down the eastern seaboard. According to his Wikipedia page, Dustin started his own wrestling career in 1988, but I like the idea of him, five, ten years earlier, looking at similar magazine pages, maybe pressing his index finger to the full-color, glossy cover in front of a pack of friends to declare that’s my father, that’s what he does for a living. Surely, the friends would have to believe. The similarities of their names aside, Dustin has always looked like the trimmer spitting image of his old man.

Similarly, I never had to convince anyone that my father and I were related. In a super-white suburb of an Upstate New York city, my father was Chinese, and despite my largely Western European facial features, I had black hair and brown-tinted skin that made me Chinese, too—the simplest categorization, no need for half-this-half-that nuance.

The similarities end there, for my father was decisively not on the road. On the contrary, growing up, I surely would have told you that he was around too much, the only stay-at-home dad I knew. The way my parents told it, they decided they wanted someone to be home when my sister and I got off the school bus, and someone to cook dinner on a consistent basis. Mom felt more of a need to get out of the house than Dad did, and so he stayed. I didn’t hear an alternative version until I was thirteen years out of the house and my mother reported that my father could be a distracted mess in the office where they had both worked as electrical engineers and that was why it was a no-brainer which of the two of them would stay home.

So, Dad watched over me as I played with my wrestling dolls after school, against a backdrop of World Class Championship Wrestling from Dallas broadcasted sporadically on ESPN. The episodes were shown out of sequence, often with gaps in programming so that it was difficult to follow the longer-term storylines. Every now and again there’d be some shift—a heel turn or title change or big debut that went missing, shifting the landscape. I had my back to the TV as often as not, kneeling at the side of the couch, colliding little plastic men against each other, recasting dolls in any number of roles to suit my purposes. Before long, I started keeping lists of my make-believe matches. Because there had to be some sort of record to make it real. So I could go back and check for my own storyline consistencies.

But as much as this play—this creative endeavor and this recordkeeping—took hold, I remember, too, a different process. It was a Saturday morning when I discovered that if I rubbed my crotch against the back of the couch while envisioning Andre the Giant bearhugging Hulk Hogan, their sweaty struggling forms pressed to each other, it created a pleasant sensation. My mother told me not to do it again. A look of disgust on her face that communicated to me whatever I’d stumbled upon was repulsive. We’d never discuss it again.

I revisited the practice on those afternoons in the living room. I remember stealing peeks at my father to be sure he was occupied with preparing dinner at the stove or reading the newspaper at the kitchen table, so I could steal humps against the couch cushion. I’d shifted my attention to the women on WCCW TV—Babydoll and Sunshine mostly—and also a pair of the first-grade teachers from school, sometimes wrapped in the same formations of wrestling, sometimes just their bodies, as I fixated on knees and forearms and the sides of Adam’s apple-less necks.

After what was probably mere weeks, but from a child’s perspective felt like years, my father told me that Mom said I was watching too much wrestling. That I had to choose between WWF on the weekends and WCCW on the weekdays, and though the latter would result in more hours of viewing, I think my parents were quite conscious that the former option was the no-brainer. I was too loyal to Hulk Hogan and “The Macho Man” Randy Savage to even consider abandoning their ever unfurling adventures.

So I stopped playing by the TV and retreated to the privacy of my room.

*

It’s been said my very particular era of wrestling fan was set up for long-term fanship in a way that few others ever have been. That my first memories would concern Hogan and Andre and Savage. That when I was a teenager, Hogan would turn heel and form the super cool New World Order that spray-painted their logo over the world title, not to mention the rise “Stone Cold” Steve Austin flipping off every authority figure who tried to tell him what to do, and The Rock probably setting a record (though I haven’t compiled the data) for the most dick jokes a wrestler has ever told to the adoring masses.

And in the liminal space between these eras, there was Goldust.

Dustin Rhodes, recast during a period when he was, in real life, estranged from his father based on a romantic relationship with a wrestling valet who Dusty didn’t approve of. Dustin Rhodes, no longer playing the part of a rugged Texan, not his father’s son any longer, but rather dressed in a shiny gold body suit, face painted in gold and black, accented by glitter. He was ostensibly named after The Gold Dust Trio—a group of high profile wrestlers and businessmen who presided over the business in the 1920s and helped establish many of the conventions of professional wrestling in America—but that’s where any sense of traditionalism died in favor of a sexually ambiguous heel who taunted foes by rubbing his chest seductively (earning ardent hatred or, in wrestling parlance, heat, from the homophobic audience) and once going so far as to administer unnecessary and unasked for mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on unconscious opponent Ahmed Johnson

By his own account, Dusty was not upset about his son’s image at that time. If anything, a wrestling star and occasional creative mastermind who helped book major promotions, he lauded his son’s ingenuity and the way in which Dustin wholeheartedly embraced this innovative role.

I think of the brief talk my father gave me, when I told him I planned to major in English at college and that I intended to be a writer. He told me he’d support me in whatever I wanted to do. Then he spent twice as long articulating how he hadn’t had that choice—how he’d felt compelled to pursue a lucrative career. The implication was clear that I was not choosing an easy life. I’ve never been sure if he was trying to change my mind.

Whatever the case may be, after I moved out of the house, I visited home for the major holidays and a period of weeks most summers during college. A bit less after that. Dad and I were never estranged, per se, but he went from a daily, dominant presence in my life to someone I didn’t see more than a handful of times in a year.

*

When he was a booker, Dusty tended to concoct indecisive ends to matches. The good guy would win only for the referee to reveal that he actually meant to count out the hero earlier, or, in the case of a championship that could only change hands by pin fall or submission, the hero would appear to force the heel into submission, only for it to turn out that the heel had cheated earlier and so was getting retroactively disqualified, so he lost the match but, by traditional pro wrestling rules, held onto his title belt.

These finishes were supposed to suggest reason for hope. That the fan favorite almost won the big one and probably should have, and it was only via technicality that the bad guy prevailed, and surely our hero would get him next time, so please, dear viewer, tune in then, or better yet plunk down your hard-earned cash at the ticket booth the next time we pass through your town.

Early on, these endings were successful. Over a period of years, the “Dusty Finish” became a pejorative term for a promoter copping out and robbing the fans of a fulfilling moment.

Dusty was in power and booking his share of Dusty finishes still in 1999. He was part of a revolving door of creative heads at the time—Eric Bischoff, Vince Russo, Ric Flair, and Kevin Sullivan also among them—who privileged shock value, leaning heavily upon twists and turns. Bischoff has claimed market research showed fans wanted, more than anything to be surprised. So, characters would turn heel with little provocation or logical rationale. During this period, actor David Arquette—an actor and lifelong wrestling fan who had starred in the WCW-produced Ready to Rumble—actually won the world championship in a publicity grabbing stunt. A couple weeks later, he turned heel when he smashed a guitar over the head of his pal who had facilitated the title win, and gifted the championship to the man who had hitherto been his nemesis.

For everything dubious about this period in professional wrestling and Dusty’s contributions to it, this was also the point at which Dustin defected from the WWF back to WCW, back to working under his father. The first time they saw each other backstage, despite not seeing one another for four years prior to that point, they collapsed into a tearful embrace.

And it would be Dustin and his half-brother Cody (same father, different mothers) who co-inducted Dusty into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2007. Long after WCW collapsed and the WWF bought up its contracts, tape library, and branding for a nominal sum. Long after the World Wrestling Federation lost a legal scuffle with the World Wildlife Foundation and rebranded under the WWE initials. After Dustin had returned to the WWE fold and reprised the Goldust character, emphasizing the eccentricity over the sexuality, after the promotion moved into what’s popularly termed the “PG era” of kid-friendly programming. Before—but not long before—Cody would set foot in a WWE ring himself. The half-brothers sung their father’s praises without inhibition or qualifiers. Cody called their dad “the greatest talker in the history of this business” and proceeded to catalog Dusty’s work as a orator, as an inspiration to the masses, a business man and a booker, before proclaiming that “if there was a hall of fame for fathers, you can bet he’d be in that one as well.”

Dusty would live on for another eight years, but for a man who’d lived most of his life in the limelight, the induction speech felt something like a eulogy.

*

Stomach cancer would turn out to be the finisher that Dusty Rhodes couldn’t overcome—not a Ric Flair Figure-Four Leglock that he could turn over and reverse the pressure on; not like Nikita Koloff’s Russian Sickle that he’d kick out from. After a prolonged struggle, after losing so much of his signature heft, Rhodes was hardly recognizable when he finally passed on June 10, 2015. But when he did, the news spread like wildfire. On his podcast, Ric Flair recalled that the family notified the WWE brass, who notified Flair, who only minutes later received a text message from friend, long-time fan, and better-known musician Darius Rucker: say it ain’t so.

Death brings people together. A moment of loss. A moment of sorrow. A moment of sweet nostalgia. WWE aired video packages of Dusty’s greatest moments on its shows that week, and rang a ten-ring-bell salute to the American Dream to kick off their Money in the Bank pay per view spectacular days later.

And when I encountered the news, I thought of my father. My father who is still mobile, who still drives his own car, and prepares his own meals, who still lives—now alone—in my childhood home. He comes from hearty stock. His mother, ninety years old, not only still lives, but cooks and cares for herself and my uncle who had his foot amputated as a result of complications related to diabetes. She still walks to a bus stop to travel to Kingdom Hall to meet with other Jehovah’s Witnesses once a week.

There’s every reason to think Dad’ll be around for a while. But still, does anyone really see a loss coming?

My paternal grandfather’s funeral was larger than my father expected for it to be—the guests included a number of Chinese friends my father had never met, never suspected existed. My grandfather better liked, better respected than Dad ever gave him credit for.

I’d grown up hearing my grandfather was stupid. That he overate until he made himself sick. That he hung in every hand of five-card draw, no matter his cards. That he was the platonic ideal of a wrestling mark, who believed for decades upon decades that wrestling was real—the outcomes not predetermined, every punch and kick not drawing blood or causing a black eye just because these wrestlers were tougher. Because they could take it.

And maybe he had reason to believe—in wrestling, in men like Dusty Rhodes, in the American Dream. Maybe my grandfather had reasons neither my father nor I ever had, because we never lived through the same hard times, never felt the same need for an escape. My grandfather watched his son grow up and grow away, better educated and better spoken. Perhaps he saw this progression in every back body drop, in my father’s every A on a report card, in every cobra clutch, in my father marrying, in every Bionic Elbow, and in the first time his son handed to him his grandson. That promise. That future.

I think Dusty would have liked that story.

Michael Chin was born and raised in Utica, New York and currently lives in Las Vegas with his wife and son. He’s the author of the new essay collection, Stories Wrestling Can Tell (Cowboy Jamboree Press, 2023) the novel, My Grandfather’s an Immigrant and So is Yours (Cowboy Jamboree Press 2021), and three previous full-length short story collections. Find him online at miketchin.com and follow him on Twitter @miketchin.

I highly recommend purchasing Stories Wrestling Can Tell by Michael Chin. I read it and love it, and so will you.

Synopsis

Professional wrestling is a spectacle. Beyond that, though, it can be a source of emotion, an inspiration, and an evocation of nostalgia. Wrestling can be a love story. And wrestling, too, can tell stories of immigration, advancement, and inheritances passed amongst family. These are the stories this essay collection shares, with forays into the absurd, the speculative, and the lines between four generations of men from the author’s family.

Please leave a comment of appreciation for Michael Chin’s poignant, moving work and share the post widely with others.

Thank you!

My mom as a kid used to be called Bionic Ears by her siblings cause she caught everyone’s conversation through the walls

Well after reading this essay and talking to you I sure am 😊