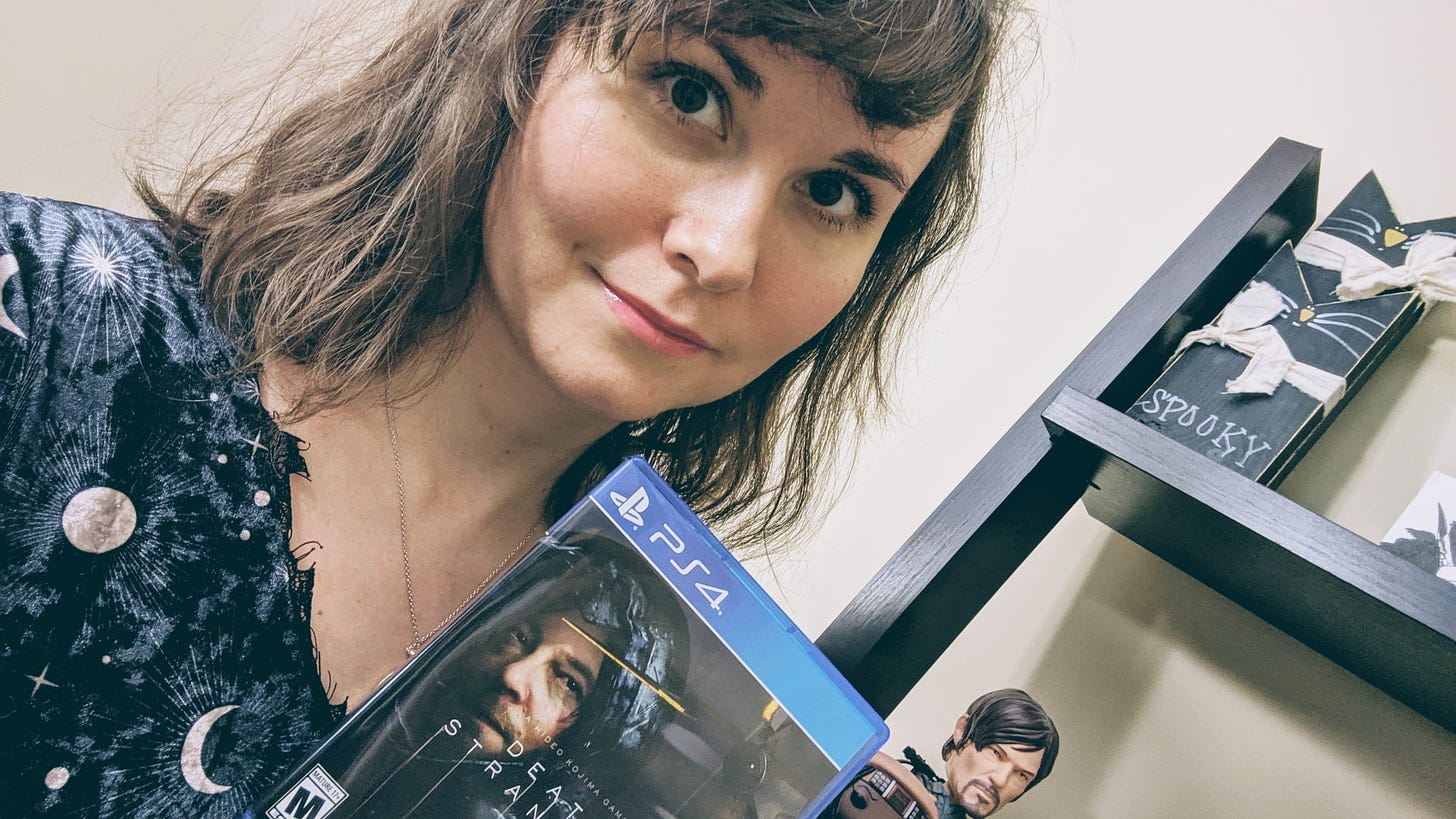

On video games, humanity, loneliness, the personal, and Death Stranding at the heart of it all

If you’re someone who yearns for connectedness, Death Stranding is for you

Dear hopeful reader,

If you’ve been subscribed to my Substack long enough, you may have noticed I have a tendency to write after poems and prose pieces particularly related to video games. I’ve been playing video games since the first time my папочка sat me in front of our first console—I was no older than six.

One of my most vivid memories was guiding him on where to go in the first Tomb Raider, a difficult game then and wildly different from the most recent installments. Somehow even then I had a knack for puzzles and environmental navigation.

I remember killing my first zombie in Resident Evil and then excitedly yelling it to my мамочка like I performed the greatest feat. It was a thrilling, terrifying adrenaline rush. The game was spine-chilling then. But even today I’m sure the pixels would scare the bejesus out of me. The remaster sure did!

The last game I played before my parents and I immigrated to Canada was the 1996’s Clock Tower. It was the first of its kind. I imagine it’s the Clock Tower franchise that gave rise to games like Amnesia, Outlast, Alien: Isolation, Remothered, among others. Games that make you feel helpless because all you can do is run away and hide. I’m not a fan of defenselessness, but I was compelled enough to play Clock Tower then. I never finished it before we moved. It got too scary for my fragile child heart!

Also read: Write a poem about an endangered animal

One of my most beloved games as a new immigrant was Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned. I played it first before I played the first second. I still haven’t played the second to complete the trilogy experience, but mostly because Tim Curry isn’t in it in any capacity. Santa—or rather my dear parents—left it for me on Christmas Eve. Waking up the next day and seeing something that shouldn’t be there but is was an exhilarating experience I’ll never forget. Especially when I’ve been anticipating it ever since I read a preview about it in a gaming journal (they were physical then!).

I lost count of how many times I escaped in the adventure that is Gabriel Knight 3. Stupidly, I gave my game with the cool box that contained it and other goodies to a boyfriend then who never returned it. So now I have this not-as-cool box with CDs I can’t run anymore because my computer is too new for that (but too old for new). The loss is felt even more now because physical PC games are no longer being made. Mostly Limited Run Games keeps physical games alive with collector’s editions of certain titles. Steam, GOG, Epic, and other sites replaced the physical with the digital, which is convenient, but it’s not the same as holding and beholding something that means dear to you, that’s tied to precious times of your past.

Jane Jensen sure knew how to pull you in with her Gabriel Knight series. She’s an author as much as she was a video game writer, designer, and director, so her approach to making games was very novelesque. Her later titles Moebius: Empire Rising and Gray Matter were narrative-driven as well. It broke my heart when I learned from the news that Jensen would no longer be making video games. It still hurts; the gaming industry isn’t quite the same without her presence and participation.

According to Vice, “The very particular path Jensen had to carve out for herself is revealing of how the industry treats its superstars. There’s no real opportunity for an independent writer-director to lead a large budget work without either submitting to employment within a massive corporate structure or building a corporate structure of their own. The industry does not give any one person power and independence at once, especially not at the scale Jensen once enjoyed.”

It’s a shame Jane Jensen couldn’t keep telling the stories she wanted in the video game medium because of the stringent bureaucracy of the industry. And it’s a shame Gabriel Knight 4 was never made, after the cliff-hanger ending in the third title, because greedy, money-hungry Activision holds the rights to Gabriel Knight but isn’t doing anything with it. There is hope Microsoft may bring back old-school games like GK once the acquisition goes through. Here’s hoping!

Before I was a reader of stories, I was a gamer of stories. The only games that electrify and engage me truly are story-heavy. Survival horror as a niche but growing genre has a lot of excellent games with powerful, transformative narratives.

The Silent Hill franchise forces us to examine our inner demons, making us play tortured antiheroes, if not antagonists, in a misty, desolate titular town that shows us our respective monstrosities and hellscapes. Resident Evil 7, the revival of the RE IP in the 21st century, focuses on Eveline and her arc to villainy, a genetically modified bio-weapon longing to forge a family. Whether this longing is genuine or a side effect of the experiment is something the players have to decide for themselves—either way, it’s heartbreaking. The Last of Us Part II explores the nuances and extremes of loss and grief. We’re coerced into powering through the intense feelings and behaviors of trauma and revenge. Even when we want to stop as players, the only way out is through.

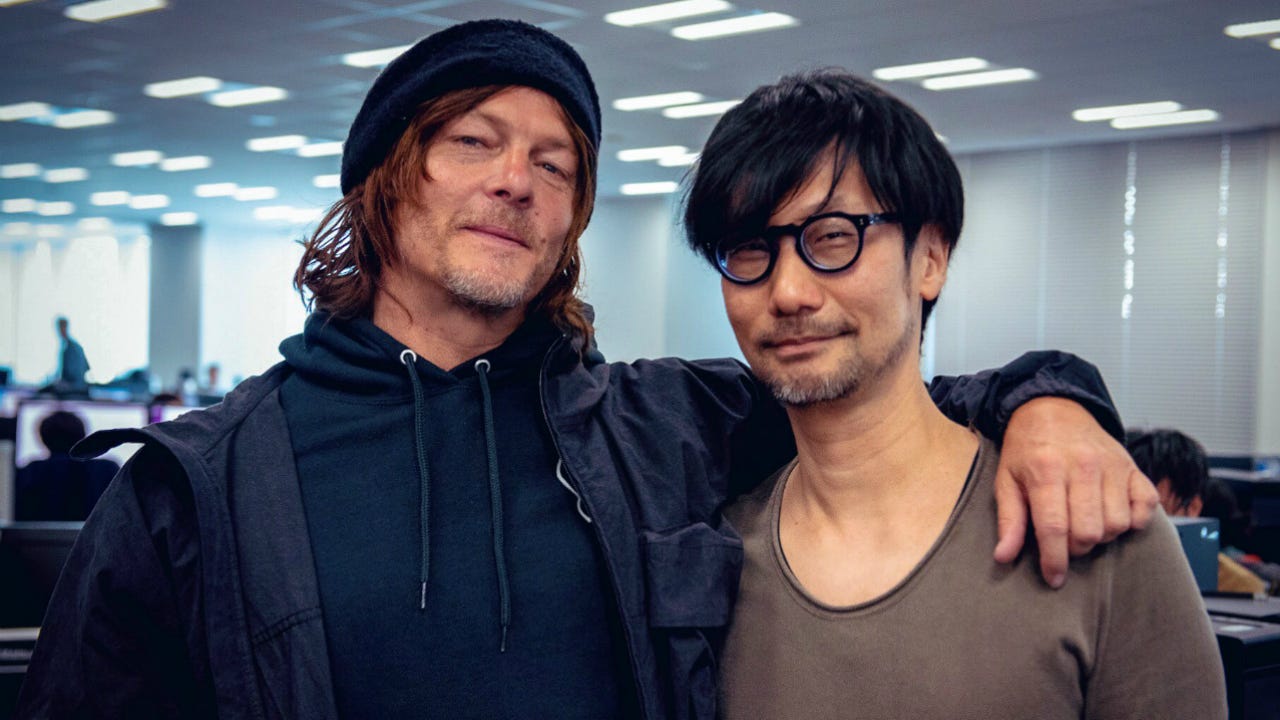

And then there’s Death Stranding, a strange, subversive cinematic experience created by the prodigious Hideo Kojima.

You should know that I don’t feel alone much. But it’s when I’m surrounded by individuals who fool me and take of me that I feel the loneliest—and I felt that a lot throughout my life. What a paradox!

Death Stranding couldn’t have come at a better time, when I needed it the most. When I greatly missed things of beauty, truth, connection, that human touch. It broke me then rebuilt me and set me on the right path to find my truth and humane-ity.

In Death Stranding you play as Sam Porter Bridges, a porter with aphenphosmphobia tasked to rebuild the broken and disjointed United Cities of America by connecting it to the Chiral Network. He has to navigate a perilous world full of rocky landscapes, unpredictable Timefalls, dangerous Beached Things, and ruthless Homo Demens to make America whole again. Meanwhile he has to overcome his fear of touch and making connections with others, learning a lot about himself and his past and that of others to make sense of today’s world and people.

If you’re someone who years for connectedness, it’s for you. If you’re missing humanity as it once was or you imagined it to be, it’s for you. If you like slow walks accompanied by ambient music from the likes of Low Roar, it’s for you. If you’re inspired by breathtaking sceneries, it’s for you. If you want horror but not too much or too little, it’s for you. If you like puzzling, poetic narratives, it’s for you. If you’re lonely or want to be or not be alone, it’s for you.

There are two remarkable features that stand out the most to me in Kojima-san’s cinematic, experiential game.

First, killing other humans has consequences in Death Stranding. If you don’t incinerate them in time—and it’s a long, risky trek to do so—they leave a crater in their wake, attracting more BTs, more danger. It’s simply not in your best interest to use lethal weapons on other people—unless to see what happens. As in a real-world setting we wouldn’t hurt anyone if we value human life, we’re careful not to do the same in DS. Because of this game mechanic, we’re compelled to think and behave in more moral, ethical ways. And as a result, anyone we encounter in the game becomes lifelike to us, causing us to see and feel their humanity, to be prudent with their personhood.

That’s a completely different approach from TLOU Part II, for instance, where you’re encouraged to kill for the sake of demonstrating the cycle of violence intrinsic to the story, and how difficult it is to break it.

The other feature is the asynchronous multiplayer system called the Social Strand System. In Death Stranding you journey alone in your mission. But over time you see objects and structures to unburden your load and make your voyage easier appear—ladders, trucks, Timefall shelters, among others—an indication there are other Sams helping one another while never actually seeing each other. You can leave or build something of yours to assist another player. To show their appreciation, they can like—as they would on Facebook—a climbing anchor you leave by a steep mountain or a safehouse you built, where they can rest after their arduous travels, and vice versa.

Also read: Flash fiction “Communications from days stranding” inspired by the cinematic masterpiece Death Stranding

There’s so much more that’s good about this system. Most importantly, you start thinking of and anticipating others’ needs. Even having never met, you know there’s someone else in need of help, and you want to lend them a hand as they would do the same for you, you imagine.

There’s a personal reason for why this system is the way it is. As a child, Hideo Kojima oftentimes felt loneliness. He struggled to express the feeling to his friends. It wasn’t something that was discussed then. Would they even understand? At one point he realized it wasn’t a sickness, but a link to others by a melancholy connection of sorts that’s specific to the human condition.

He conveyed that connection and loneliness so well in the game. We’re alone, and maybe lonely, and we’re not. We’re separate but also together. Contradictory, and yet, it makes sense. Now I understand what I’ve been feeling through the years.

All my life I’ve been searching for deep connections and community. I was cultivating that when I was running my own publication not too long ago. Sharing beautiful art and writing and empowering others with words of encouragement and friendship is all I ever wanted. But like the world of Death Stranding, the online literary community became too toxic and disconnected for me to continue to be a part of it as of late.

I made mistakes along the way, and some dark slivers penetrated my soul, influencing me to act hastily and irrationally, when my intention was to always be good to others. I’ve seen it happen to other genuine, kind, well-meaning folks as well. I still see it happen from afar.

Online we stop seeing each other as we are—humans—when there’s a wall of the computer screen that separates us. Becoming more detached from our humanity, we have no problem spewing hateful words, ungrounded labels, menacing threats, calls for cancellation, and irrational boycotts, more often than not being unaware of the full story of something we’re advocating for or against, not fully knowing our target—their heart, their intention, their life, their struggles of their own. If it means someone loses their livelihood or life, it’s not compassion that inspires these actions.

I’m ashamed and regret to have ever participated in acts like these in the past when I thought I was standing up for kindness. I can only redeem myself by acting with kindness, forethought, and wisdom now. Even when someone may act unkindly towards me, I don’t need to stoop to this level myself, how ever easy it can be.

When I left the lit community and deleted most of my social media accounts, and kept close only those whose hearts I know are good and genuine, I became a recluse. I was broken, insecure, and scared in some ways. I also forwent my online magazine of almost five years, which was a big loss for me. And I still feel devastated for all the wonderful work I published that disappeared with its vanishing.

A lot of my thought processes before involved how others would think about and react to a situation, but not always how I felt and perceived it, all on my own. Often it was fear-based: to be afraid of hurting someone and to also be afraid of being hurt. Over time however, as I learned more about myself and the world around me, I gradually remade myself. I’m truer to who I am now more than I have ever been.

In personal relationships I’m not assertive, and I struggle with setting boundaries. Instead I’m all about being diplomatic and gentle in my interactions, especially when getting around an awkward or unpleasant interaction. Occasionally I find the courage to advocate for myself when necessary. Before I thought I was being weak. Today I embrace being tactful, sensitive, and adaptable with others. I’m assertive where it matters the most in my life—in my profession and in my marriage.

I believe in the power of listening to others. Not just hearing, but actually listening. It’s when we listen to others that we truly understand their intent. After leaving the online community I was a part of, I promised to myself to further develop my listening skills, and become a much clearer, calmer communicator. We’re feeling humans, so it’s inevitable for all kinds of emotions to arise in an upsetting situation. We can still be respectful to our interlocutor while honoring our feelings.

When I started my Substack almost three months ago, I also promised to myself to never alienate anyone and treat everyone with dignity and humanity. My mission with “when hope writes” is to explore the nuances and layers of our humanity with nonjudgment and to inspire hope in others. I want everyone to feel included and united here, and I hope you do. Death Stranding gave me a light push in 2019, and here I am today.

In Death Stranding we’re eventually made to understand there are no clear villains. The antagonists we come into contact with are rather complicated, broken individuals fighting for their beliefs in a ravaged world. They’re humanized. Whether that’s good or bad is up for debate.

One thing is clear: humans are complicated. I imagine Hideo Kojima meant to create characters who are complex, nuanced, and layered, how we are in real life. He meant for us to empathize with them, as we would in reality. He meant for us to to be gentler with ourselves and others after playing Death Stranding. And whether it takes us one day or several years, I hope we do handle each other with care as we would a precious cargo. And as we do, maybe we’ll become more unified and less lonely.

Is there a piece of art that affected you so much your whole life altered?

Yours hopefully,

Nadia

Wow Nadia. I am 100% honest when I say that reading this was the first time I felt a spark today.

I am not a video game person - in fact never played one unless the arcades are considered video games. I always thought them to be violent and pointless but your post made me feel like insanely wrong.

I had no idea you have so much stories and value inside video games. And you are such a great writer to convey those facets of life so beautifully. I felt like I was reading some old diary of mine ( it felt so connected). I wish I could have read your old magazine contents but I am happy for you as it must have been a very hard decision to delete old writings. I can say that you are living up to your expectations and you are making everyone feel included. I can personally say that as you have been showering me with love on my posts. There are times when knowing that someone is effected ( positively) by your work, you feel hopeful.

So grateful for your hopeful writing. I will be reading every post of yours even when I have no idea how to play any video game.

Thanks for reminding me of the importance of games in our lives! I'm more of a board gamer, but have lived computer games and RPGs through my husband & son (and even wrote a MG novel about a kid who writes RPGs). For me, the art that most affects me is music, always. Elgar's cello concerto played by the brilliant and tragic Jacqueline du Pre, in particular, whom I tried to emulate when I played it myself.